Swarming Season

May and June are busy times for beekeepers as this is when our bee colonies may try to swarm. Swarming is the natural way that a colony reproduces itself. The worker bees gorge themselves on honey from their stores, and then the queen departs with about half the bees, leaving the rest of the colony to produce a new queen. The old queen and the bees who went with her will cluster on a tree or a fence while scout bees look for a new home. At this time a beekeeper can capture the swarm and put it in a hive to start a new colony. If you’re hoping to produce honey you don’t want to lose half your bees and a load of honey in a swarm. So we need to be vigilant and look out for early signs that the colony is getting ready to swarm, then try to trick them into thinking that they have already swarmed, and there are several methods for doing this.

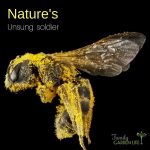

The photo shows one of my colonies getting ready to swarm. The flat, biscuit-coloured cells in the comb are where worker bee larvae are developing. The first sign of preparations for swarming is the development of drones (male bees) and the cells containing these have bulging, yellowish wax cappings. Some of these are visible at the bottom of the frame. The colony then prepares for the old queen departing by producing new queens. Queen cells are the long, finger-shaped cells of which at least 5 are present in this photo. Each is capable of hatching a new queen. A beekeeper will usually leave one or two of the best looking ones and remove the rest, otherwise there is a possibility that as each new queen hatches she leaves as a swarm with another portion of your bees.

We need to check our beehives every few days throughout these months and be ready to do the “artificial swarm” manoeuvres or we risk losing a lot of bees and much of our honey crop.